With these new collections, 2015 has proven a particularly rich year for poets writing against the geographically and culturally Anglo-Saxon grain of the English language. All three poets slip between loved languages, confronting readers of British poetry not only with words and turns-of-phrase borrowed from other idioms, but alternative ‘Englishes’ – ways of speaking that highlight how thinly the language covers a far more linguistically diverse world.

At one level, the second language surfacing in each collection represents a tug on the poet, a different chamber of the heart. For Sarah Howe, Cantonese permeates her poems both as a lost language and a language of loss. “Yut, ye, sam, sei”, she counts in ‘Crossing from Guangdong’ (Howe 2-5), “like a baby”. Numbers, with their connotations of mortality, conjure lost persons. In this case, Howe hears her mother’s voice, “almost / querulous, asking me not to go”.

Points of reconnection are not only heard but seen. Howe’s poem ‘Drawn with a very fine camelhair brush’ (Howe 39-41) captures in sonorous English the visual sensuousness of the Chinese language. She marvels slowly at the “fletched fir of tree”, and “the strung / crescent of moon”, as well as “two jewelled eyes” that form the characters for ‘dragonfly’. Just as the mandarin at the heart of the narrative is at once captivated and frustrated by the dragonflies’ “marriage of stillness and furious motion”, Howe is enraptured by Mandarin while struggling with the “mistranslation” of moving between tongues.

A similar argument plays out between Kathleen Jamie’s two selves. In ‘World Tree’ (Jamie 37), she addresses the tree that “marked (her) world’s end” as a child, and wonders if it was “elder or hawthorn, bour or may”. ‘Bour’ is Scots for elder, and ‘May’ for haw; both trees have deep roots in Celtic lore, but reappear among the leaves of English literature. It is this linguistic entanglement that, “like a beggar at the bottom of our lane”, stalks Jamie even in adulthood. “How odd”, she muses in ‘Scotland’s Splendour’ (Jamie 49-50), “to feel its weight once more”.

Unlike Howe’s Cantonese, Scots is for Jamie a language regained, not lost. Because this occurs in the politically charged present, her questions are as much of selfhood as sovereignty. The poem ‘23/9/14’ (Jamie 41) comes immediately after Scotland’s unsuccessful independence referendum. Her penultimate line, written in Scots, is hopeful: “We ken a’ that. It’s Tuesday. On wir feet”. Conversely, in ‘Wings over Scotland’ (jamie 51), she meticulously lists the names of chemicals which have killed birds of prey. Here the absence of Scots, coupled with terse, technical English, highlights a new, painful unfamiliarity in Scotland’s denuded skies.

Nancy Campbell’s writing comes from a different place. She arrives in Greenland with a visitor’s gaze, and falls in love. She is, in a way, the “wild inquisitor” from the north in her poem ‘The Message’ (Campbell 27), “dressed…in (her) own breath”. It is in the snowstorm, when London’s familiar landscape becomes an arctic one, that the polar inclinations of Campbell’s English consciousness are tenderly revealed. In an intriguing pairing, the poem on the facing page, ‘Seven Words for Winter’ (Campbell 26), presents English translations of seven Greenlandic terms: Campbell has made familiar what is coldest and harshest about this other land.

All three poets, however, reject a simple binary between English and their second languages. Formally and thematically, they borrow extensively from the canons of world literature to foreground the counterpoint explored above. In ‘Gale’ (Jamie 59), Jamie alludes to haiku with a short, stark poem derived from a broken question-and-answer: “Whit seek ye here? / There’s noucht hid i’ wir skelly lums / bar jaikies’ nests”. Likewise, throughout her collection, Howe reaches for the tomes and times of Roethke, Borges, Foucault, and Pound. She challenges directly the idea that belonging can be located in one culture or another, preferring the unflinching honesty of “a personal Babel: a muddle”.

On this note, Campbell’s work proves most interesting. She gives a sense that she has plumbed the history of her own language, and found something foreign there. Near the end of Disko Bay are ‘Two Old Riddles’ (Campbell 57-58), translations of Anglo-Saxon enigmata. Both riddles point to elements far from our modern imaginations of Middle Earth: an iceberg and tsunami respectively. Here, layered over unfamiliar contours of Old English, is a suggestion that the texts’ original scribes knew a radically different ‘England’. Campbell responds with ‘Two New Riddles’ (Campbell 59-60) of her own, that return the reader to the cosmopolitan present, from which the worlds of Japanese artisans and deep geological time prove equally accessible.

2015 has seen Britain’s poets develop increasingly cosmopolitan threads within the English language, drawing from their own experiences and the cutting-edge of literary scholarship to widen its bounds. It is through their work that English, though rooted as ever in its North Atlantic soil, will become the testing-ground for new ideas of belonging.

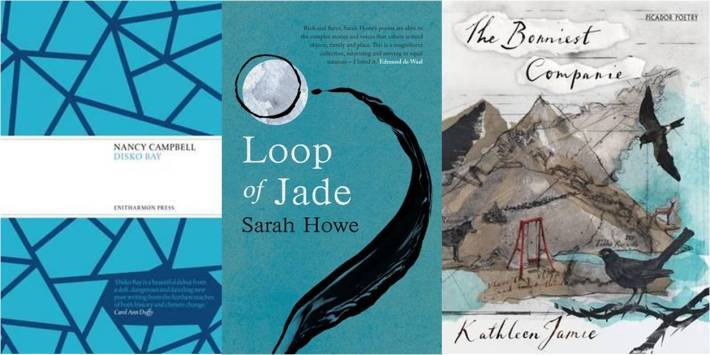

Nancy Campbell. Disko Bay. London: Enitharmon Press, 2015.

Sarah Howe. Loop of Jade. London: Random House, 2015.

Kathleen Jamie. The Bonniest Companie. London: Picador, 2015.

Theophilus Kwek is the author of two collections, They Speak Only Our Mother Tongue (2011) and Circle Line (2013). He is the current President of the Oxford University Poetry Society.